Navigation

Let's Start with the Basics

Let's face it - behavior can be confusing. It can be difficult to understand why it's happening or what we can do to change it. However, even the most complex human behavior comes down to a few basic principles:

- All behavior has a reason. Behavior exists in order to meet a need.

- All behavior is learned. This is because all behavior is either rewarded or punished, whether intentionally or not. Therefore, we need to teach the behavior we want to see.

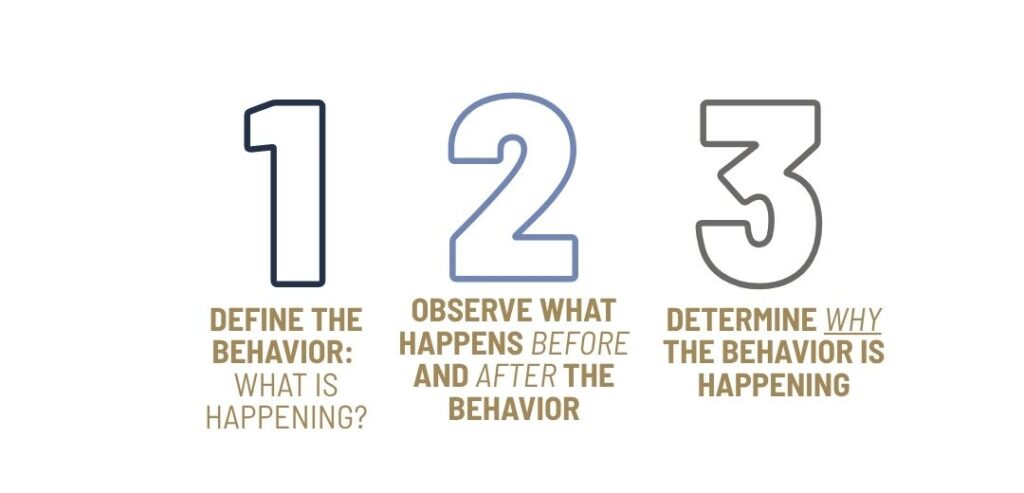

Once we understand the underlying principles of behavior, we can follow these 3 steps to analyze a specific behavior before we create a plan to change it:

The ABCs of Behavior

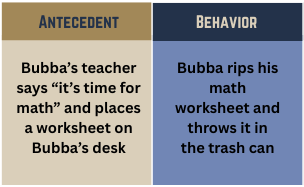

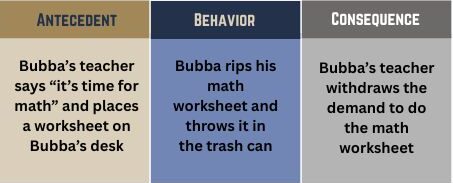

The ABCs of behavior are defined as the Antecedent, the Behavior, and the Consequence. These terms apply to every single human behavior. We'll start with the behavior itself and then dig into what happens before and after.

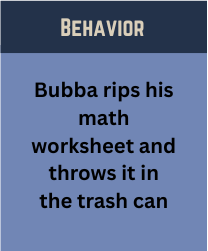

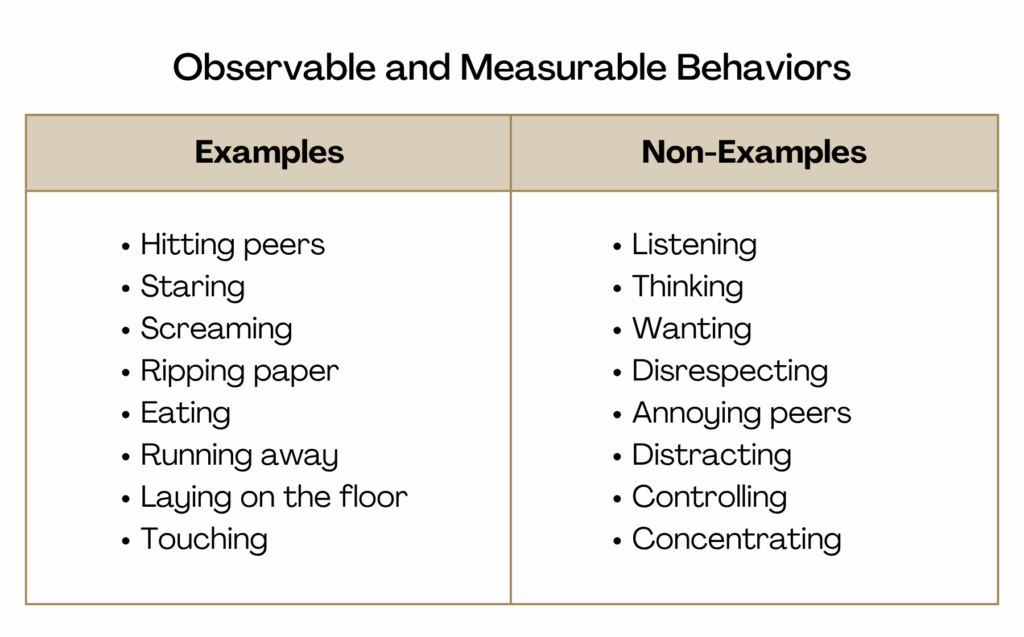

Behavior

A behavior is anything a student does that can be observed and measured. Behavior can be positive (i.e. staying on task, following a direction, etc.) or negative (i.e. hitting, running away, or ripping up a paper.)

We use the phrase "problem behavior" to refer to a behavior that we wish to change.

When defining a behavior, be as specific and objective as possible. Avoid using words that are emotionally charged, vague, or that have a variety of meanings or interpretations.

Antecedent

An antecedent is an event or condition that occurs right before a behavior. Think of it as what sets the stage for or triggers the behavior. An antecedent can be (a) something that happens to the student or (b) something important that does not happen.

Here are some common antecedents we see in the school setting:

- A task or work demand

- Being told "no"

- The end of a preferred activity

- The start of a non-preferred activity

- A task that is too hard or too long for the student's current abilities

- A negative peer interaction

- Lack of adult or peer attention

- A verbal reprimand

- A punishment or loss of privilege

- A long transition or wait time

- Unclear expectations or routines

After finding the antecedent, we'll look at what happens after the behavior in order to determine how the behavior is or is not being reinforced.

Consequence

Often, those in education use the word "consequence" as a synonym for "disciplinary action." But when it comes to behavior, a consequence simply refers to what happens immediately after a behavior.

A consequence can increase or decrease the likelihood of a behavior's occurrence, depending on whether or not it feels good for the person experiencing it. Therefore, we look to consequences to see what might be reinforcing a behavior.

Can you see how Bubba's teacher may be inadvertently rewarding Bubba for ripping his paper? Because she responded by removing the math assignment altogether, Bubba may be more likely to rip his paper again in the future.

Reinforcement and Punishment

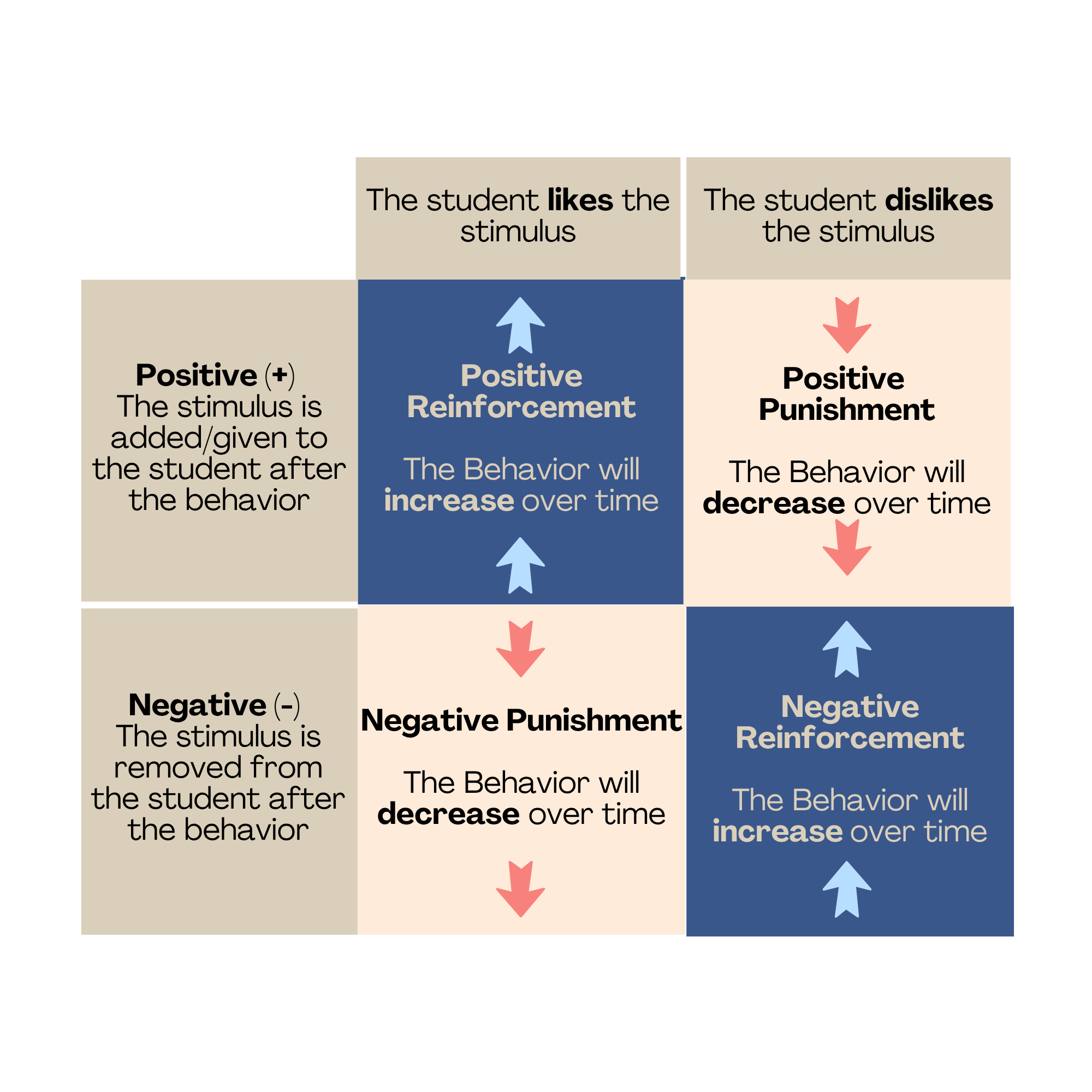

Consequences can be divided into reinforcement and punishment.

Reinforcement refers to a consequence that increases the likelihood of a behavior's occurrence. It feels good to the individual experiencing it and therefore they will want to engage in the behavior again.

Likewise, punishment refers to a consequence that decreases the likelihood of a behavior's occurrence. It does not feel good to the individual experiencing it and therefore they will want to avoid the punishment in the future.

Both reinforcement and punishment can be considered positive or negative. This refers to whether a stimulus is applied or removed following a behavior. Take a look at the chart below to further understand this concept.

In Bubba's case, the stimulus - his math assignment - was removed. Let's say Bubba dislikes this stimulus. The consequence for Bubba's behavior can therefore be considered negative reinforcement. This will most likely cause an increase in Bubba's problem behavior.

The Power of Reinforcement

When responding to problem behaviors in the classroom, we can very easily find ourselves leaning heavily on punishments. However, research shows that it is more effective and productive to use positive reinforcement to increase a desired behavior than it is to use punishment to decrease an undesirable one. This is because punishment stops behavior but only reinforcement changes behavior.

Children who engage in problem behaviors are more likely to engage in an appropriate replacement behavior if we can make it more reinforcing to them than the problem behavior.

Next we will look at how consequences can serve as a key into why a student is engaging in a particular behavior.

Functions of Behavior

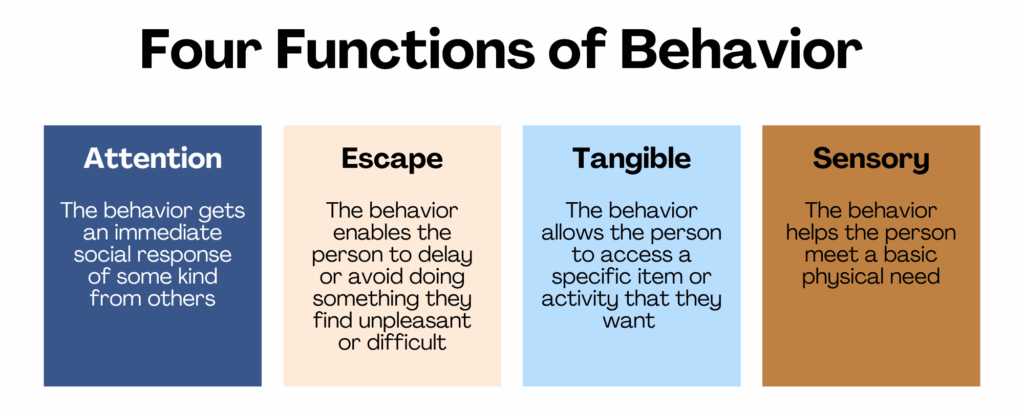

All behavior has a reason and exists to meet a need, or function. These functions can be split into four categories:

- Access to Attention

- Escape from Something Undesired

- Access to Tangibles or Activities

- Access to Sensory Stimulation

(Definitions taken from the LRBI.)

If a student's individual needs are not being met through an appropriate behavior, they may engage in problem behavior in order to meet their need in the easiest and quickest way possible.

As we know from discussing consequences, problem behaviors have been reinforced by the way people have responded to them. Over time, if our response to a problem behavior is meeting a child's needs more efficiently than our response to their appropriate behavior, the problem behavior will become more prevalent.

Once we understand the unmet need behind a behavior, we can 1) adjust how we respond to the behavior, and 2) teach a new behavior that meets the same need. As we reinforce the new behavior more frequently, we will see it eventually replace the problem behavior.

1. Attention

The goal of attention-seeking is to gain the attention of another person, typically of an adult or a peer. This attention can be positive or negative.

Simply denying the student attention will not make their need for attention go away. Instead, we need to give the student attention when they seek it in a more appropriate way.

Example: A student is shouting out in class in order to gain attention. We may be tempted to respond to this by correcting the student. However, a correction would provide negative attention and reinforce the shouting out. Instead, we could ignore the shouting out while teaching the student to raise their hand for attention. Removing our reinforcement for the problem behavior while adding reinforcement for the replacement behavior will allow the hand raising to replace the shouting out over time.

2. Escape

An escape-maintained behavior allows a student to avoid or delay something that they find unpleasant, difficult, or otherwise aversive. For example, a student may run out of the room in order to escape work that they perceive as being too hard.

When addressing escape-maintained behaviors, it is important to provide our student with an appropriate way to escape while we teach them how to better handle or cope with the aversive stimulus.

Example: A student elopes from the classroom in order to avoid doing math work. Our long-term goal would be for the student to stay in their seat and complete their work without eloping, but this doesn't address the function of the student's behavior. Therefore, in the meantime, we could teach the student to ask for a break instead of eloping. The break would meet the student's need to escape the task in a safer and more appropriate way, while we work with the student on other strategies such as asking for help.

3. Access to Tangibles or Activities

Behaviors with a tangible function provide a student access to an item or activity that they want. These behaviors occur when a student desires a particular reinforcer and may escalate when that reinforcer is denied or removed. For example, a student may engage in physical aggression towards an adult in order to gain access to an iPad the adult is holding.

Addressing a behavior with a tangible function involves teaching a student a more appropriate way to gain access to the thing that they want. This involves teaching functional communication skills as well as skills like waiting and handling "no."

Example: A student hits their teacher when their request for a particular toy is denied. This student may be taught to request the item appropriately or to wait to access that reinforcer until a specific time or until they have earned it. After they have accessed the reinforcer, they may be provided with a transition activity or item or rewarded for relinquishing access to the reinforcer.

4. Sensory Stimulation

Sensory-driven behaviors are those that help a student gain or avoid sensory stimulation. These behaviors provide "Automatic" reinforcement, which means they reinforce themselves without requiring help from other people. For example, a student may run from the room in order to avoid loud noises in the classroom, or they may create loud noises through banging on their desk in order to stimulate themselves.

Many sensory-driven behaviors are completely harmless and provide little to no distraction to others, such as hand-flapping or rocking back and forth. However, if a behavior is harmful or excessively distracting, a student can be taught to replace the behavior with something equally stimulating but more appropriate.

Example: A student hits himself in the head when he hears loud noises that are aversive to him. This student can be taught to wear headphones throughout the day and to ask to leave the room to go on a walking break when loud noises are present. He can then be rewarded for having a safe body.

What's Next?

You've learned about the basic principles of behavior and what causes a behavior to occur more or less frequently. Take some time to map out the function of your student's behavior, as well as common antecedents and consequences. Are there any ways in which your student's behavior has been reinforced unintentionally? Think about some specific strategies for teaching replacement behaviors.